The great Catholic philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre passed away this week; may he rest in the peace of God. They always tell you to never write a dissertation about a writer who is still living- because the author can write something new and there goes your dissertation! I ignored that sound advice and wrote a dissertation on Alasdair MacIntyre's work, because his ideas are so fascinating (here is an article version of a dissertation chapter I did for Perspectives on Political Science, and a review of MacIntyre’s last book in the After Virtue series I did for the CRB).

I never got to meet and thank Alasdair MacIntyre in person (I was too shy). However:

I did get to ask him a question across the room once at one of his Notre Dame Center for Ethics and Culture conference lectures (I described that exchange having to do with the common good here on the Pomocon Substack).

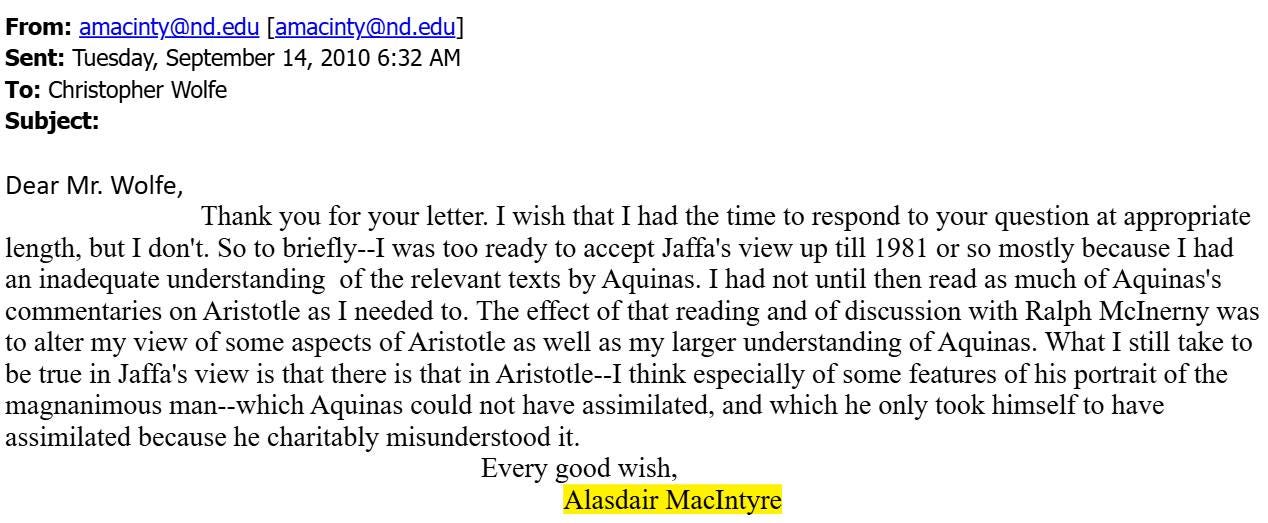

I wrote him a letter- and he sent back a wonderful email, which I share below. I emailed him a second time to ask him if I could share the letter (he said yes), but I have never shared it publicly until now.

By way of background: As someone who got a mainly Straussian political science education at Claremont, I wrote to ask MacIntyre what he thought of Harry Jaffa’s book Thomism and Aristotelianism in 2010. When MacIntyre wrote the 1984 Postscript to the 2nd edition of After Virtue, before he had reverted to Catholicism and adopted Thomism as his philosophy, he stated his reasons for not doing so:“From the moment that biblical religion and Aristotelianism encountered one another the question of the relationship of claims about the human virtues to claims about divine law and divine commandments required an answer. Any reconciliation of biblical theology and Aristotelianism would have to sustain a defence of the thesis that only a life constituted in key part by obedience to law could be such as to exhibit fully those virtues without which human beings cannot achieve their telos. Any justified rejection of such a reconciliation would have to give reasons for denying that thesis. The classic statement and defence of that thesis is of course by Aquinas; and the most cogent statement of the case against it is in an unduly neglected minor modern classic, Harry V. Jaffa's commentary on Aquinas' commentary on the Nicomacbean Ethics, Thomism and Aristotelianism (Chicago, 1952).” (p278)

Something had to have changed from 1984 when he wrote that- and 2010 when he had accepted Catholicism and Thomism. So I wrote MacIntyre and asked what had changed- he wrote me back this wonderful letter. Enjoy:

b“Dear Mr. Wolfe,

Thank you for your letter. I wish that I had the time to respond to your question at appropriate length, but I don't. So to briefly--I was too ready to accept Jaffa's view up till 1981 or so mostly because I had an inadequate understanding of the relevant texts by Aquinas. I had not until then read as much of Aquinas's commentaries on Aristotle as I needed to. The effect of that reading and of discussion with Ralph McInerny was to alter my view of some aspects of Aristotle as well as my larger understanding of Aquinas. What I still take to be true in Jaffa's view is that there is that in Aristotle--I think especially of some features of his portrait of the magnanimous man--which Aquinas could not have assimilated, and which he only took himself to have assimilated because he charitably misunderstood it.

Every good wish,

Alasdair MacIntyre”

Wow, CJ! I agree, I think, w/ AM's characterization of Aquinas's "charitable misunderstanding" of the magnanimous man.

A book I have on my shelf, but haven't gotten around to, is Natural Reason and Natural Law: An Assessment of the Straussian Critique of Thomas Aquinas, by James Carey. He sides with Aquinas against Jaffa. Carey is not widely known, but when I did my master's degree at St. John's College, Santa Fe, he seemed to me the wisest teacher there, with only David Bolotin coming close. As Eastern Orthodox, though, he had his own set of criticisms of Aquinas.